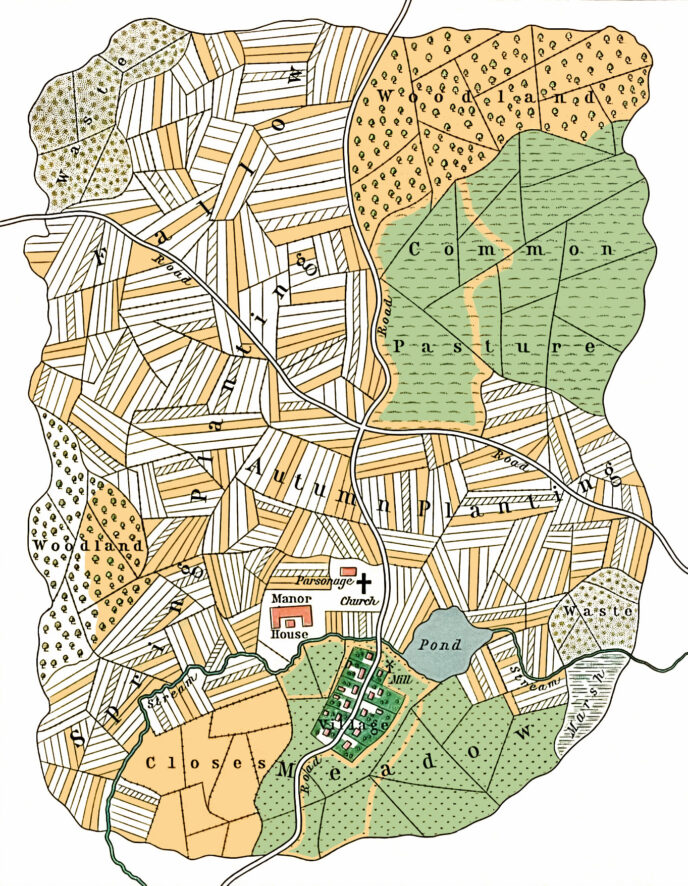

8% of the land in Wales is specified as ‘common land’ . It is a shared access space that is not built on and provides access to nature and in some instances for farming. There can be rules to how the space is used such as a shared licence for farming, however it may be a self-regulating space or system .

Many of the common spaces in Wales are owned privately or by the National Trust. There is usually a right for people to access the spaces but the land owners hold the value of any resources or the land value. The UK Monarchy, for instance, own land which generates income which has had an increasing value .

There are a few commons in south Wales’ post-industrial areas , including in Pontypridd.

A meeting place

The Pontypridd commons staged a neo-druid movement early in the 19th century, which Evan Davies (who created the stone circle), William Price (doctor and activist), and Evan and James James (composers of Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau) were a part.

Figure two: an election campaign meeting for Labour candidate C.B. Stanton at the Pontypridd common. Image from the People’s Collection Wales, © Pontypridd Library 2023.

In 1814, stones were placed around a rocking stone that was already in the common. Gatherings were organised at the space, including regular meetings for people living locally and weekly lessons of the Welsh language; as an intervention against moves to quash Welsh being spoken in the area .

Continuing as a place for civic association 1, the area acted as a meeting place for activists and campaigners later that century .

Are they sustainable?

William Forster Lloyd and Garrett Hardin have written about their research and thought about how when a space or resource is shared, that humans using the space will act selfishly when making decisions about using the resource. Unless there are rules or regulations dictating behaviour . Donnella Meadows talks about a bounded rationality which may be causing this – that we can only see other elements and links in a system that are close to ours. That we cannot see all parts of the system. A farmer in a commons may decide to add more sheep based on the information they have available, but may not see the overall impact of that decision (if all the farmers decide the same, the commons’ resources deplete!) .

Rules, regulation, and domestic land ownership (if you own it, you look after it) are interventions to create sustainable management of spaces. However, there seems to be a lack of evidence that there is a problem with shared ownership spaces, particularly if there is a conversation, association, and information shared between (links) the people (elements) that use the space (the system).

This land is your land and this land is my land

Woody Guthrie

From California to the New York island

From the redwood forest to the Gulf Stream waters

This land was made for you and me

A common space without rules could be behaving like an anarchy, a place with no rules and depending on people (not government) to figure out their differences .

Comparing the common land to other types of spaces, there doesn’t appear to be additional or dissimilar conflict. Land ownership and rules applied by the land owners may not be the only intervention to the tragedy of the commons. Particularly when considering the planet (and sustainable use of land) as a whole.

Along with accessible information about the state of the space (to support decision making), a framework such as the Future Generations Act’s Well-being Goals could be used by people (such as the sheep farmer) when making decisions about the commons. Particularly the goals of: cohesive communities and global responsibility . With this Design Innovation framework, people making decisions do not need to see beyond their part of the system.

In Wales, particularly in areas that have unused spaces, the use of current and creation of new commons could support prosperity to local economies .

There seems to be possible innovation in these spaces. The Pontypridd commons shows us that these spaces can be a place to create connection, in a free to use (which could be an) inclusive space.

With this I wonder: should there be more scrutiny of the commons in Wales? Is there transparency about who owns the land and how they are benefiting from it? And what is the potential of the commons in Wales?

Notes

Note 1: In Making Democracy Work, Robert Putnam’s research observes that citizens in areas that form civic associations and live in a civic community are “trustful toward one another, even when they differ on matters of substance”. People are more considerate of others and willing to compromise on their own political stance or opinion. They tend to be happier: “happiness is living in a civic community”. A civic association is the forming of a group of individuals for reciprocity; such as a “choral society” .

This appears similar to bridging social capital: individuals and groups that connect with others (other individuals or groups) horizontally that are usually divided (such as the protected characteristics). Bridging social capital is outward looking, it is an outlook and action which creates a sharing of ideas and opportunities – it fosters equality and harmony .

Note 2: this post was included as part of an assignment for my Masters. It includes amendments made on 4 February 2025.

1 Pingback