Industrial Revolution

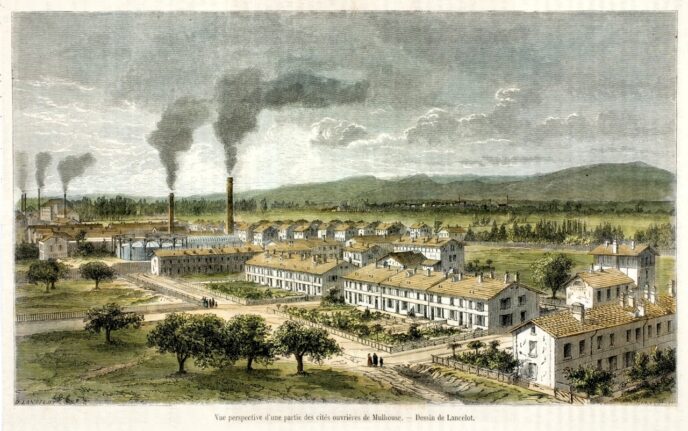

As people started to move to cities due to industrial work, the need for urban parks increased and legislation created to allow Councils to create space for recreation . In some areas, Industrialists built model villages for their employees to provide what they perceived as a better life outside of work. These villages usually had green spaces for recreation and gardens for individuals to grow produce (figure one) .

Post-industrial

In cities that were becoming post-industrial, as in Cardiff, the park spaces grew when private gardens were opened to the public. However, at roughly the same time, an increase in the number of privately owned cars changed the way people used their local spaces. It became popular to leave the area towards other spaces for recreation, such as National Parks . Urban parks became a place for tourism.

Although there is legislation allowing for urban parks, there isn’t legislation requiring Councils to provide these spaces. Cuts to public services over several decades have led to the condition of urban parks in the UK to degrade .

Councils (such as Cardiff Council) have turned to income generation from commercial avenues to top-up their budgets, using the public space as a resource .

Future cities

Urban parks became more popular during Covid-19 lockdowns and some architects at the time suggested redesigning parks to encourage and incorporate social distancing. Following Covid-19, it could be that a more compact city will be desired .

The numbers increased so much during covid because people could keep six foot from each other and, and walk in a park. You’d see people doing the, you know, the circuit going up through the Bute Park Llandaff fields, back around [to], Sophia Gardens.

I think research has been done into the the benefits of using parks for mental health … it helped me anyway, just walking around every day.

Paul, Interviewee, Friends of Bute Park

The UN’s Sustainable Development goal 11 calls for cities to be “safe, resilient, and sustainable”, including a target to provide universal access to “green and public spaces” .

In Guadalajara, Mexico, a network of urban forests has been created with the hope of reducing CO2. Parts of the city near one of the forests experience temperature of “2 or 3 degrees less” (Guadalajara’s Urban Forests Network, [no date]). Cities can be recognised as a Tree City by following 5 standards towards how trees are protected and managed by a Council .

With flooding happening more frequently and, at the same time, clean water becoming more difficult to access, the urban park is changing. Such as in Wuhan, China, where the city has removed flood defence walls and replaced them with a beach park which acts as a park and the space absorbs the water when needed .

In Rotterdam, the Netherlands, the city is adding green spaces to rooftop spaces to “make the city more livable” and to help with its “climate challenges” (figure three). Different colours (or categories) for each rooftop outlines different functions, such as “social cohesion” or “delayed drainage”. Measurable benefits are found supported by the Multifunctional Rooftops Tool, including annual reduced water treatment costs .

Approaching urban planning in a non-linear way, in creating a circular economy within a city, urban parks are changed and fixed depending on the need of the moment . Our post-industrial cities in Wales can be redesigned and repurposed to suit the modern-day demands.

Reflection

The model villages of the Industrial Revolution extended the idea of an urban park to the streets and to the abode. Although I have attempted to focus on the urban park here, other categories will overlap or contribute to this observation. How we use or see a park will be closely linked to the common land, street, or garden .

The urban park seems integral to urban design, a space for civic association 1, for nature, and to support city zero emission targets. The space is recognised as important currently and has potential for future need.

To realise the potential of the urban park, changes to law or policy may be needed to reverse the degradation of the land and use of the spaces, so that they are prioritised for budget and seen as part of the solution for sustainable development in Wales.

Notes

Note 1: In Making Democracy Work, Robert Putnam’s research observes that citizens in areas that form civic associations and live in a civic community are “trustful toward one another, even when they differ on matters of substance”. People are more considerate of others and willing to compromise on their own political stance or opinion. They tend to be happier: “happiness is living in a civic community”. A civic association is the forming of a group of individuals for reciprocity; such as a “choral society” .

This appears similar to bridging social capital: individuals and groups that connect with others (other individuals or groups) horizontally that are usually divided (such as the protected characteristics). Bridging social capital is outward looking, it is an outlook and action which creates a sharing of ideas and opportunities – it fosters equality and harmony .

Note 2: this post was included as part of an assignment for my Masters. It includes amendments made on 4 February 2025.